3 MIN READ

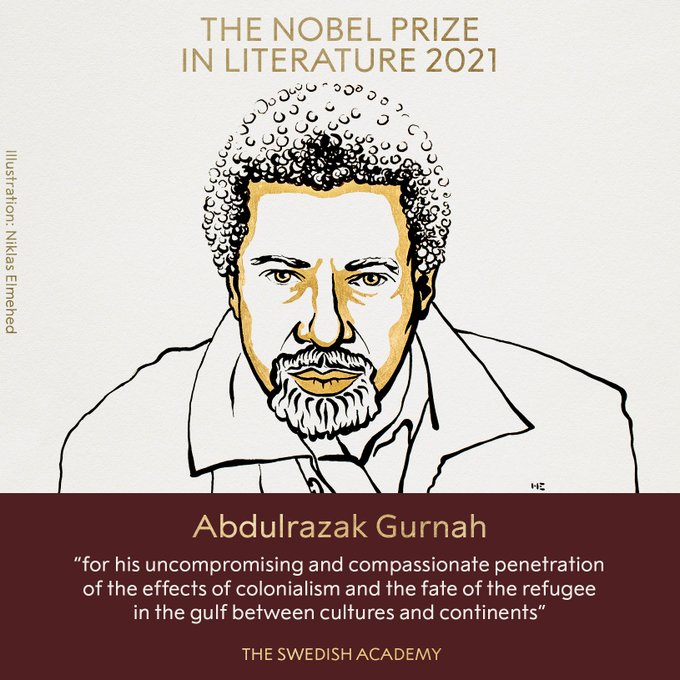

As it is known, this year’s Nobel Prize in Literature has been given to the novelist Abdulrazak Gurnah for his prolific storytelling work on exile and refugee life journeys meeting new cultures and challenges, the works very much inspired by his own and other refugee lives. Originally from Tanzania or a former Zanzibar island, the writer has been living and writing in England since he fled his home country in 1968. All the books he began to write in his twenties are in English although English is not his mother tongue. I often think it must take a genius individual to be able to express oneself and write literature in a foreign language. The writer’s native language is Swahili – the widest spoken language in the African region.

Swahili, or Kiswahili, is considered the most important language of East Africa spoken and understood by millions. The official language of Tanzania and Kenya is also largely used in Uganda, Rwanda, and Burundi. It seems common for African regions of numerous ethnic groups to speak Swahili as the first language, especially in urban and mixed areas. I have been lucky to have had a smattering of Swahili through teacher JC originally from the Democratic Republic of Congo. There the language, also called Zaïre Swahili, is spoken by more than 11 million people, mostly in eastern regions of the country. The people of DRC speak a host of regional dialects, such as Katanga Swahili, Kivu Swahili, or, for instance, Kingwana, a pidgin* Swahili. JC used to quote to his students one South African president who believed the Swahili language should be an official Panafrican language to unify all African people.

Swahili is one of the Bantu languages and originates from the large Niger-Congo language family. Though its vocabulary is mostly Bantu, many words are of Arabic origin. The name Swahili means “coastal” in Arabic, used by the Arabic-speaking settlers of the African coast in about the 7th century. Later, during the 19th century, traders brought it further inland, and it was adopted as the language of administration in the state of Tanganyika (present-day Tanzania).

When speaking of Swahili, the first thing most likely that comes to mind is the phrase hakuna matata meaning ‘no worries,‘ used in the animation film The Lion King from 1994 or in the hit song from the 80s Jambo Bwana by the Kenyan band Them Mushrooms. Learning Swahili should be indeed no worries for an English speaker. The pronunciation is quite easy to acquire, and the grammar rules are easily digestible. The most distinct grammar feature of the Swahili language is the rule to have all grammatical inflections (word parts, e.g. endings to mark singular and plural by adding -s in English) at the beginning of the word. The words fall into classes, 18 in total: the so-called Ki Vi class, e.g., kiti – a chair, viti – chairs, or the M Mi class as in mkono – arm, mikono – arms, and the M Wa class mainly in words for people, e.g., mtoto – child, watoto – children. These features are used with nouns as well as verbs, adjectives, and numerals. Numerals, numbers and weekdays, are notably different in Swahili spoken in African countries of Islamic culture and those of predominant Christian culture: e.g., number nine is kenda in Tanzania, but tisa in Congo.

A quick scroll down of the list of writers awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature clearly shows the predominance of the most common languages the winners have written their works in, with a few exceptions of Czech, Icelandic, and Provençal**. Swahili – a fascinating language of great importance and a great number of speakers, though not yet, I somehow sense will be added to the list one day.

**

*A pidgin language is a common language shared by several groups of speakers of different languages who simplify its grammar and vocabulary to communicate easier.

** Provençal – a dialect of Occitan language spoken by minority people of France in Provence.

Sources: Ethnologue, The Swedish Academy, The Languages of the World by Kenneth Katzner (1975)