11 MIN READ

Watching the BBC’s I can’t say my name (stammering in the spotlight) made me seriously think about and dedicate this month’s post to speech production and pronunciation. From severe speech impediments that require treatment to innocent speech errors that occur every now and then are not unfamiliar to most of us.

Every spoken language is produced by making sounds that appear in our mouths with the help of vocal cords, tongue, teeth, uvula, lips, nose. We may argue that as long as we have these parts of the body functioning, we are able to produce sounds that form comprehensible and meaningful speech to express what’s on our minds.

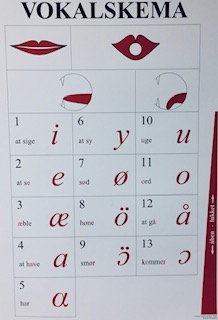

Speech sounds are either consonants produced by an obstruction in our mouths or vowels produced with no obstruction by simply letting the air out. Most languages have more consonants than vowels and distinguish between them, which may at times be challenging, especially when it comes to vowels (In Danish, for example, there are three distinct ways of pronouncing vowel a). Click sounds in African languages and dialects such as Xhosa and Nǀuu are pronounced with a click of the tongue against the teeth or a kiss-click made with lips and represent a type of consonant. In sign languages too, consonants and vowels are distinguished and spelled using fingers (dactylology) either by one or two hands.

Pronunciation is one of the language learning process parts. Especially when keeping in mind that the most learn a foreign language nowadays namely for communication purposes, i.e., people aim to be heard and understood. Our pronunciation and the way we sound may have an impact on how others perceive us. It gives an impression of who we are and how we feel. Research suggests it to be a possible deciding factor in the outcome of exams, trials, and job interviews.

Danish Vowels

Often, when learning a new language, we become familiar with phonic rules and study a phonetic transcription system. If you have never heard of it but already master several foreign languages, such a set of rules, also called a phonemic chart, is not a bad idea to resort to when learning a language. It helps to better understand the place and manner of articulation of consonants, or quantity and quality of vowels, of what is happening in our mouths in general when we make sounds, and learn the ways that help us achieve that impeccable native-like pronunciation. Sounds are studied by phonology and phonetics. Phonology has its focus on studies of sounds as a part of language and processes affecting pronunciation of words, while phonetics is, above all, interested in physical and physiological aspects of sounds and the way they are produced and perceived.

As children, we acquire language without learning the rules and yet learn perfect pronunciation. Children, though, make some either consistent or variable “errors” or deviations in speech production when acquiring their native language (early sounds sound rather different from those produced by adults. As my little brother, who today is an eloquent speaker of several languages, growing up had his own ingenious ways of saying the simplest words and according to our family records his lapa was for labas (hello) and himself he called tavo (yours) instead of aš (I)). However, there are cases when children never develop language skills and suffer from a condition called Specific Language Impairment (SLI) when a person’s development of language is obstructed for no clear or fathomable reasons.

The most common speech errors, both in our native language and foreign language, that all of us may make is when tongue-twistering, e.g., quickly saying Peggy Babcock multiple times in a row. Here bilabial (p b) and velar (k g) plosive consonants are being challenged and can easily be interchanged. Another famous example of a tongue twister is He threw three free throws. In Lithuanian, we have an equivalent šešios žąsys su šešiais žąsyčiais (six geese with six little geese) , and the similar one just recently learned reading Latvian Nora Ikstena’s novel is Latvian šaursliežu dzelzceļš (narrow-gauge railway), both challenge the ability to distinguish between palato-alveolar fricatives sh and zh. Tongue twisters can be good fun and practice. In Danish, foreigners amuse themselves trying to pronounce rødgrød med fløde (red porridge with cream) where a lot is going on in our mouth trying to make through the pharyngeal r and /ð/-the so-called “soft d.” Youtube has plenty of entertaining videos of people attempting to pronounce it. However, saying the innocent rugbrød, which means rye bread makes my eyes large and my mouth dry every time I need to buy one, whole four years later. And it doesn’t make the situation any better and end my despondency when a bakery assistant switches to English right after, assuming it is safest to do. Something tells me I should go back to practicing my Danish tongue twisters even harder.

Other times when speaking, it is either we make anticipations, and we utter a sound anticipated from the following word, or perseverations when we repeat a sound from an earlier pronounced word, or we substitute, add or omit some sounds in the words we spontaneously pipe up. Spoonerism is an example of a speech error named after a lecturer at Oxford University, William Spooner, who is rumored to have made errors of exchanging two sets of sounds in consecutive words, e.g., You have tasted the whole worm instead of wasted the whole term.

English writer Lewis Carroll is known for his playful and inventive use of language. In the preface to his nonsense poem The Hunting of the Snark (1876), he himself explains the pronunciation of the coined words and suggests a “Humpty-Dumpty’s theory, of two meanings packed into one word like a portmanteau” taken from his other poem Jabberwocky (1871), like the word frumious which consists of two words fuming and furious merged into one. The author suggests that if you have “a perfectly balanced mind, you will say “frumious” instead of saying either fuming-furious if your mind happens to be inclined towards fuming, or if towards furious, you are likely to say furious-fuming.

Without rest or pause–while those frumious jaws

Went savagely snapping around-

He skipped and he hopped, and he floundered and flopped,

Till fainting he fell to the ground.

(Fit the Seventh – The Banker’s Fate, The Hunting of the Snark by L. Carroll)

So it seems that a well-functioning mouth mechanism is not sufficient to produce fluent speech. The brain, and mind as in Lewis Carroll’s case, is an active participant in the speech process, too. Different brain areas communicate with each other as well as co-operate with the muscles that control breathing and speaking. This teamwork must be excellent to produce the right sounds, words, and sentences with the right rhythm, pauses, stress, and accentuation, making the speech flow and smooth.

A consonant or several consonants together with a vowel form a syllable, and in case there are more consonants bound together as in straw, we call it (consonant) cluster. Syllables then consequently form words and word combinations that may be challenging to pronounce both in our native and especially in a new foreign language. But can we blame it all on challenging sounds? Imagine you sit in a language class having a great idea and the correct answer, memorized and carefully picked out vocabulary together with impeccable and grammatically correct formulated sentence, but once you open the mouth you stumble over an unpronounceable sound combination. The teacher seems puzzled, there is silence in the classroom, your frustration together with the affective filter* is skyrocketing, and your confidence is plummeting. The affective filter is a so-called stage-fright feeling and panic whenever one needs to perform in front of the audience. When the affective filter is high, a mix of awful emotions jumbles up, the ones like annoyance, frustration, anxiety, stress, and the language teachers’ task of a speaking class is to lower that filter whenever and as much as possible to make the classroom environment welcoming even for making mistakes. Otherwise, there may be no sound produced in the classroom.

A little stress does cause certain errors in speech. I personally sound different depending on the language I use, the interlocutor, and the situation. I hear myself pronounce the same words differently when teaching the language compared to doing interpreting work in it. Once, when in exotic Svalbard to chase the Northern Light and by all means avoid meeting a polar bear, during one of the day trips to desolate mountains and an ice cave, shockingly, astonishingly, I and apparently my brain got frozen to the point where I was struggling to pick the right words when talking to our English speaking tour guide. The freezing temperature and exhaustion clearly impacted my frozen brain and its function. A truly unforgettable trip in many possible ways reminisces my now thawed memory.

The frontal lobe and the parietal lobe of the human brain is where language is produced and understood, respectively, mainly Broca’s area, Wernicke’s area, and a path connecting the two, the Arcuate Fasciculus, all located on the left side. If these parts of the brain get somehow affected or injured, it may result in serious speech defects. The most severe language disorders are aphasia (agrammatism, paragrammatism) and Specific Language Impairment (SLI).** These are continuously studied, particularly by neurolinguists, and as the brain is such a complex organ, science seems never to cease examining it. If we suffer from any speech and language impairments, from language delay, learning difficulties such as dyslexia to aphasia and SLI, we turn to a speech-language pathologist or therapist for treatment.

Stammering or stuttering*** remains to this day a mysterious condition despite being a common speech problem, especially in childhood. A curious fact is that it is more common in boys than girls, the reasons for which are still unclear. However, it is claimed besides that it may be genetically inherited, to be caused by neurological reasons. According to NHS, the National Health Service in the UK, speech-related problems happen when the development of speech areas in the brain are not in balance and do not work together. This causes repetitions, stoppages, or lack of sound produced when a child is excited, stressed or needs to say a lot. The film The King’s Speech from 2010 follows the journey of UK King George VI overcoming his speech impediment, and US President Joe Biden has long been vocal and open about his struggle as a stutter. Making it more public may help improve knowledge about this speech difficulty. Hopefully, those who suffer from it make it less shameful and embarrassing, and those who don’t, gain a better understanding and tolerance.

One thing is clear – speech production is a rather complex and significant matter. We all may be touched by it and struggle with producing speech in one way or the other, in one situation or the other. It is worth remembering that it can not always be taken for granted. Practice, patience, hard work and effort, empathy, and sometimes even treatment are required to make it work.

- If teaching language – tongue twisters as phonological practice; lowering the affective filter as much as possible may be a good idea;

- If learning language – a phonemic chart to master the pronunciation; tongue twisters as fun specific articulation activities; if learning English, check out The Perception of Spoken English (POSE) test

***

*The hypothesis by linguist Stephen Krashen suggesting that a learner’s anxiety, low self-esteem, or lack of motivation can be a mental stumble block preventing the successful acquisition of a second language. If the affective filter is lowered by creating a welcoming and motivating learning environment, the learners are more likely to acquire a foreign language.

** Aphasia – a disorder of language and speech caused by a brain lesion which may be due to an accident or a stroke after language has been acquired and functioned normally; SLI – the opposite to aphasia is a disorder before normal acquisition of language has been developed and without there being any clear primary deficit; agrammatism (Broca’s aphasia) – a condition when the patient omits function words such as articles or grammatical inflections with no effect on content words such as nouns, verbs, and adjectives; the opposite is paragrammatism (Wernicke’s aphasia) which does not affect grammar and function words but a patient seems fluent making long sentences with errors in content-word usage, i.e. paraphasias.

***Stammer is a British term, stutter used in American English as well as in New Zealand and Australia

Sources: NHS; BBC; TESOL course material (ASU); Linguistics. Introduction, second edition, A. Radford et al., p. 12, 114-115, 213-217; The Language Instinct. How the Mind Creates Language, Steven Pinker, 2007