9 MIN READ

News nowadays is overwhelmed reporting about the events in the tumultuous world and their impact on it. Once in a while, when news on language sneaks in, a language enthusiast is instantly all ears and immensely intrigued and entertained. Earlier in January, the television news network Euronews reported some glad tidings for the Irish language speakers and activists.

It was with regard to the first hearing at the EU’s top court held in the Irish language on January 14. Besides, it was not only that the case had been held in Irish, but it concerned the Irish language itself.

According to Euronews, the case that has reached the European Court of Justice is a complaint about the Irish government misinterpreting and failing to implement EU rules that require labeling on veterinary products to be in official languages. Both Irish and English are official languages of the state, but the Irish government has used only English. The current developments in Luxembourg have left Irish language activists thrilled, especially before the language gains its full status as an EU language in 2022.

The feud between the Irish government and the Irish language proponents has been long-standing. If one wonders why, some argue that the reason is the government’s negligence due to too few speakers of the language which is “in grave peril” and on the brink of extinction altogether. Interestingly, the data provided by Kenneth Katzner in his book The Languages of the World from 1975 claims there were 500,000 people, about one-sixth of the population, who spoke the language in the Republic of Ireland at the time. According to the language data register Ethnologue*, currently, there are known about 141,000 native and first-language (L1) Irish speakers in the Republic. Perhaps it is not strikingly many for the population of less than 5 million for the language to compete on equal terms with the dominant English, and it will make the smallest official fully-fledged working language of the EU institutions. There are, however, 1,200,290 (170,290 as L1 and as 1,030,000 as L2) users in total worldwide, spoken not only in Ireland but also in New Zealand, UK, and the USA.

Further, Ethnologue states that Irish is the statutory language of national identity (Constitution, 1937) and its status is threatened. Speakers are mostly adults. And though it is taught as an official language in schools and many children learn the language, the number of young speakers seems to be decreasing. English having a position as the statutory national language is considered the first official language of Ireland, suggesting its dominance and superiority.

Irish, also called Erse, Gaelic, Gaelic Irish, Irish Gaelic, is classified as Indo-European -Italo-Celtic- Celtic-Insular -Goidelic-Irish Gaelic and spoken in the numerous counties such as Cork, Meath, and Waterford, also on western isles northwest and southwest coasts. Its siblings are Scottish Gaelic and Manx languages.

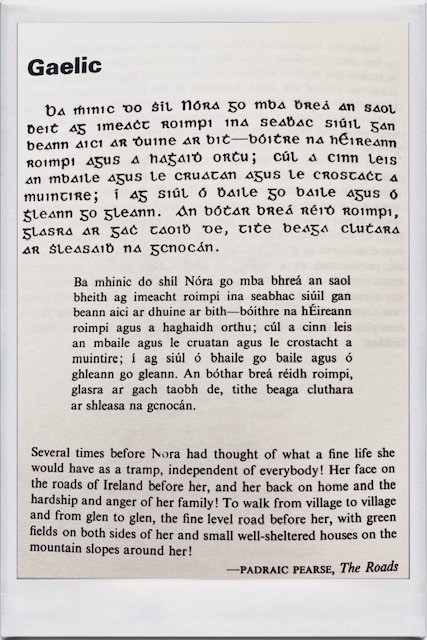

Here we can see the example of Irish Gaelic, first written in the traditional Gaelic alphabet and then the same text in modern English characters followed by the English translation below.

If we compare the Irish Gaelic text to the English translation, they look anything but similar. I, personally, cannot detect any familiar word. The Gaelic alphabet shown at the top of the example derived from Latin in about the 5th century. It consists of five vowels and thirteen consonants where the letters j, k, q, v, w, x, y, and z are missing. The most significant difference between Irish Gaelic and English, arguably, may be a sentence structure. Irish Gaelic is the VSO language meaning that the sentence structure goes like this: Verb-Subject-Object. The English sentence, e.g., I read a book follows the Subject-Verb-Object (SVO) structure, when in Irish Gaelic, the sentence would be Léigh (Verb -to read) mé (Subject-I) leabhar (Object-a book).

English has adopted Gaelic origin words such as bard, glen, galore, slogan, and whiskey, to name some examples.

Northern Ireland, which has been a part of the UK after the partition of Ireland in 1921, has, according to the 2011 UK census, 184,898 (10.65%) people who claim to have some knowledge of Irish. Here it is recognized as a minority language, and the dialect spoken is known as Ulster Irish (Gaeilge Uladh). Ethnologue reports that most speakers are found in Armagh county, Belfast, Fermanagh and Omagh county, as well as some in England and Wales. It is widely used as a second language (L2) in all parts of Northern Ireland, but with status as threatened.

Back in the Republic of Ireland, there are a number of Irish-language organizations, led by the Coimisinéir Teanga, Language Commissioner, whose main objective is to promote and protect the language rights of Irish and English speakers, advance the 2003 Official Languages Act and ensure that the Act serves speakers of both languages. Nevertheless, it seems that there have been too few vocal promoters of the Irish language until possibly the EU role using it will turn the tide. Many famous writers and poets that we think of as English were or are, in fact, Irish. And it is mainly because their writings have been in English. The list is long: Jonathan Swift (1667–1745), the author of Gulliver’s Travels; the famous and glamorous Oscar Wilde (1845–1900); James Joyce (1882–1941), who is regarded as one of the most influential writers of the 20th Century, the author of the epic novel, Ullyses, and the collection of short stories, Dubliners; poet William Butler Yeats (1865–1939) one of Irish Nobel Prize winners; George Bernard Shaw (1856–1950) who was quite an influential figure in early 20th century London and author of famous plays Arms and the Man, Man and Superman, and Pygmalion; another playwright and Nobel Prize winner Samuel Beckett (1906–1989), best known for his plays such as Waiting for Godot, who spent most of his adult life in France and wrote in both French and English; Edna O’Brien (1932) has produced remarkable contemporary novels such as Girl with Green Eyes and The Country Girls; the acclaimed names of new generation writers such as Sally Rooney and Colm Tóibín.

There is a handful of those who wrote in Irish and promoted the Irish language and culture. J.M. Synge (1871–1909) was a major figure in the Irish Literary Revival and one of the founders of the Abbey Theatre in Dublin. He wrote some of the most famous and significant Irish plays – The Playboy of the Western World, In the Shadow of the Glen and Riders to the Sea. Poet, playwright, and short-story writer Brendan Behan (1923–1964) is too regarded as one of the greatest Irish writers who wrote many of his stories and plays in Irish, including his most famous book Borstal Boy.

The example of the text in the picture above is The Roads by Patrick Henry Pearse (also known as Pádraig ) (1879–1916) who was an Irish teacher, barrister, poet, writer, nationalist, republican political activist, and revolutionary and after his execution seen by many as the symbol of the rebellion. Pearse wrote stories and poems in both Irish and English. Among his best-known English poems, such as The Mother, The Fool, and The Rebel, he wrote several allegorical plays in Irish.

The language to live on and thrive needs to be used, both spoken and written. The future of the Irish language can be promising, with the biggest EU institution playing a significant role in using it and hence requiring specialists, translators and interpreters, and a growing audience. It will be exhilarating to wait and watch further developments in later pieces of news on the language.

*

*Ethnologue– a reference work/catalog in print and online that provides data and profiles on the world’s languages.

Sources: The Irish Times (2014), Wikipedia, Ethnologue, Kenneth Katzner’s “The Languages of the World“