What a better day to start writing a language blog than today, February 21, the International Mother Language Day. You might think I should then better be writing it in my mother tongue (which is Lithuanian, by the way – a tiny Indo-European Baltic language which might even be in the process of shrinking and becoming vulnerable, especially within Lithuanian borders), but in my defense, IMLD (International Mother Language Day) is something to be aware of and celebrated, and what better way to do it than to spread the word about it in a lingua franca.

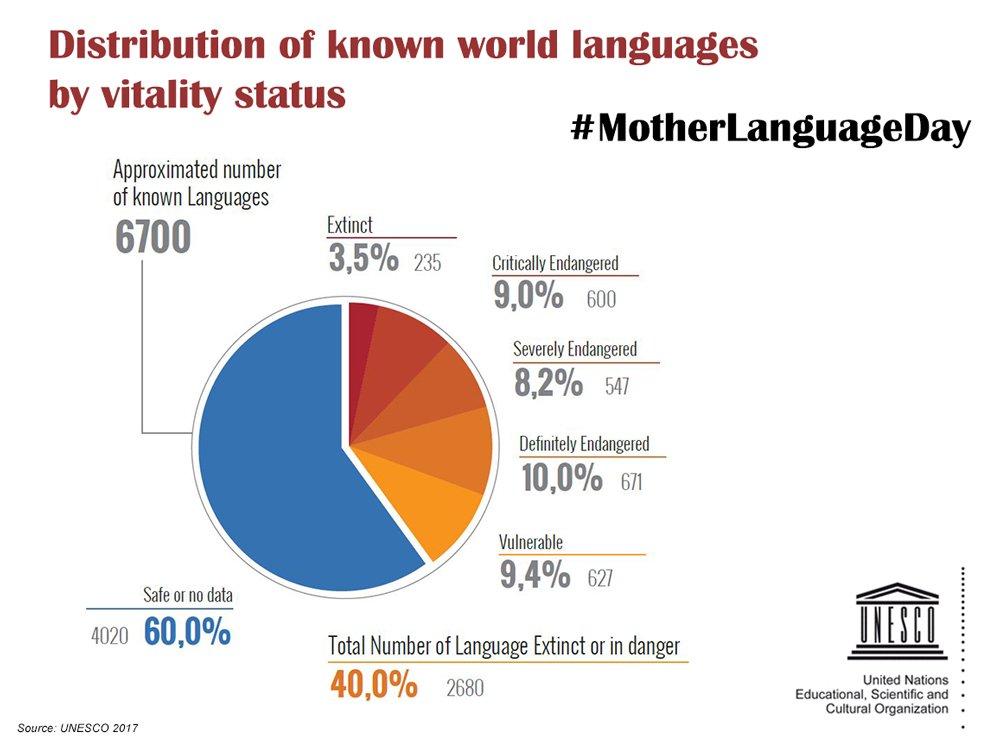

IMLD is about promoting multilingualism and linguistic as well as cultural diversity. UNESCO warns that linguistic diversity is increasingly under threat as languages simply are disappearing. About 40% of the world languages are endangered or extinct. The organization is continuously emphasizing the importance of education, especially the primary one, being accessed in a mother tongue, with some progress made.

The idea to celebrate IMLD was initiated in Bangladesh for recognition for the Bangla language when in 1999, the initiative was approved by UNESCO and soon recognized worldwide. February 21 is a national holiday in Bangladesh to commemorate the tragic events of 1952 when protesters were killed and injured during the Bengali Language Movement in East Pakistan (now Bangladesh). Those people have actually sacrificed their lives for their mother tongue.

The term “mother language” or “mother tongue” or “native language” (also known as arterial language or L1) is used for the language that we learn as children. Can we call that language “father language”/”father tongue”, and what if we are born into a bilingual family, where parents speak to us in two different languages? Well, apparently, there are different names to call it and ways to define what that language is, depending on ethnicity, birthplace, etc. Some experiments have been made to prove that babies hear all mother’s sounds, including her voice, from around the sixth month of baby’s living in the womb. They do not hear the clear words, but they can hear the rhythm and intonation, picking up the very first features of their mother’s and eventually their mother language.

Looking at my internationally mixed friends’ families, I can definitely claim I see examples of a “father tongue” which children are best at and most comfortable expressing themselves in simply because they are being engulfed in the language of their father’s country of origin where they are born, raised and schooled.

In my case, as someone born to parents who speak the same language, I have a tendency to use words of my mother’s dialect and even borrow some features of her idiolect*. Though, interestingly, I do not notice the same tendencies in my brother’s use of language. More questions related to mother-child connection and child’s initial language acquisition pop up in my head: what about children born in one country and adopted in another to the parents that possess different language, what about those born to surrogate mothers? Are there any rudiments of the first language in such cases?

Interacting in a natural way with a child is key to language further development. As babies, we begin to imitate our mother’s (or father’s) language we hear while acquiring our first sounds, words, intonation. When a baby is born, their ears are receptive to all the sounds of every language. Brain imaging technology research has shown that the relationship between a child’s exposure to language and their brain development is interdependent. According to what languages they are exposed to, the neural pathways are either strengthened or weaken and die off. By hearing something over and over again, children learn the structure of a language, and eventually, it gets hardwired into their brains.

There are no tests to measure how native a speaker is, but according to specialists, a native speaker is one who is fluent, spontaneous, has intuitive knowledge of the language, and no foreign accent, but most importantly acquired the language in early childhood and maintains the use of it. Considering this, we can define the difference between a native language speaker and a fluent one. It can be significant when defining the level of language skills of the one who teaches a language as well as of the one who learns it and benefits from certain language learning methods.

It can also be relevant for primary school children. Access to primary education in a mother language is not only the way to maintain and preserve it but also the way for young children to learn best. International schools, for instance, are wonderful in many ways in terms of quality of education, which is often given and received in a non-mother language, be it English, French or German, and the students are not necessarily native speakers of those languages. I see the importance of the knowledge about the world, particulary the primary one, acquired in a language we understand best and have the best sense for. This way, the flux of new information we receive reaches our brain without any impediments until it lodges there, gets processed, digested, and eventually translated into multiple other languages we learn along the way.

*Idiolect – unique speech habits of a particular individual

Sources: UNESCO; Wikipedia; David Crystal “A Little Book of Language”, Dr. Particia Kuhl’s studies.